Web content accessibility is rarely prioritised when creating designs, and very few websites are accessible. In 2008, 70% of the sites reviewed by the Business Disability Forum were assessed as lacking accessibility.

I think there are four main reasons why UK companies don’t invest in designing for accessibility:

- Currently, it is only a legal requirement for public sector bodies.

- There is additional design, development, and testing effort required to comply with accessibility standards.

- Many lack the experience designing for accessibility.

- The complexity of accessibility guidelines can seem overwhelming.

In this post, I explore three ways of approaching accessibility that make achieving it more manageable. Firstly, making your web content accessible can be achieved gradually. Secondly, the design stages suggested in the WCAG standards are flexible and allow scope for creativity and interpretation so they can be achieved in a variety of ways. Lastly, designing for accessibility helps us create better designs as it forces us to better understand our users, which as UX designers we should always seek to do.

1. Disability is a spectrum

Disability is a spectrum. It can be temporary like having a broken arm or more permanent like being colour-blind. It can be situational like being in a loud crowd. It can have different levels of severity from being short-sighted to having complete vision loss. Microsoft published booklets that give a good overview of what disability is and how inclusive design can be used as a methodology to create more accessible designs.

According to gov.uk, 1 in 5 people in the UK has some form of disability. When we think of accessibility as a spectrum, we can start perceiving it as something we can work towards and something that we can achieve incrementally. We can gradually move on the accessibility spectrum to get closer to fully accessible web content.

While the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG 2.1 guidelines]) are not presented on a continuous spectrum, they are nonetheless, structured as stages. Each of its guidelines is assigned a priority level based on its impact on accessibility (Level A, level AA, level AAA).

You can use automated testing tools like axe to get an idea about how accessible your web content is, but you have to delve into the detailed guidelines for a proper assessment of the accessibility level of your web content.

In terms of being WCAG 2.1 compliant, you must have satisfied all the requirements for one level before moving to the next. This means that you can start focusing on level A accessibility standards, which cuts down, by more than half, the amount of material you need to look at initially.

However, even though the levels need to be completed consecutively, you should be aiming to, satisfy requirements across all three levels. Designing for accessibility should not be a box ticking exercise but rather should help ensure that web content is accessible to as many people as possible from the target user group(s). This brings me to the second point that I think we should consider.

2. Guidelines not rules

WCAG are guidelines rather than rules. Some of the guidelines are very technical and quantifiable in terms of what criteria to meet. However, many require an interpretation based on the context, this makes the judgement about whether the guidelines have been met in such cases more subjective.

For example, the 1.4.12 WCAG 2.1 guideline states that the line height has to be at least 1.5 times the font size. This is a very explicit criterion that we can easily test for. On the other hand, guideline 1.3.1 states that “Information, structure, and relationships conveyed through presentation can be programmatically determined or are available in text”. This guideline relies on how we perceive and understand information. This element of human cognition makes it more difficult to assess compliance with some guidelines.

However, this is where, as UX designers, we can play a very important role. To determine the best way of presenting information in order to make it understandable, we identify the context within which users acquire that information. We think about who will be using the information, what they will be using it for, how they will use it and in what context.

For example, if you have web content that will be displayed on a monitor, you may need to add audio to make it more accessible. Whereas, the same content intended to be used on a desktop, may require that you consider keyboard support.

This is the sort of thought process needed for interpreting some of the accessibility guidelines and translating them into actionable design decisions. A UX-lead approach means you’re already on the path to making your content accessible.

3. Better designs for everyone

As UX Designers, we often consider many of the accessibility guidelines like colour contrast, text size, and legibility. However, with that, we only scratch the surface. Our deliberation when it comes to designing for accessibility has to go beyond that because this will allow us to create better designs for everyone.

Being aware of the accessibility guidelines allows us to make better design decisions and to reassess some of the design decisions we have made. It can highlight things we might have not considered, and that would make the design more understandable for everyone.

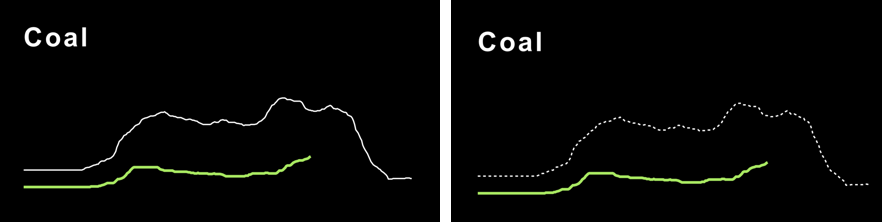

I recently worked on a redesign of a site to make it more accessible. In the original design, a line chart with 2 lines comparing today and yesterday’s data was presented. The only difference between the 2 lines was the colour. When I looked at guideline 1.4.1 about the user of colour, I learned that colour should not be used as the only visual means of conveying information, indicating an action, prompting a response, or distinguishing a visual element. Something as simple as making one of the lines dotted can make a big difference. Colour blind people would now find it easier to distinguish between the 2 lines.

Example of using dotted lines to create a visual differentiation between two lines in addition to colour

Sometimes small design tweaks can go a long way in making web content more accessible, which would benefit all users across the accessibility spectrum. Designing for accessibility and meeting accessibility standards can be done incrementally so don’t be afraid to start the process.